Between 2020 and 2025, I used MyChart almost every day. It wasn’t optional. It wasn’t a “nice to have.” It was the front door to my care.

During the height of COVID, MyChart wasn’t just a portal — it was how you qualified to receive treatment. Before stepping foot into MD Anderson, I had to complete screenings through the system: symptom questionnaires, exposure checks, appointment confirmations. If you didn’t pass the digital gate, you didn’t enter the building. Temperature checks and in-person screening followed, but the process started online.

When you’re undergoing cancer treatment, especially during a pandemic, tools like this aren’t conveniences. They are infrastructure.

They’re how you communicate with your care team.

How you receive test results.

How you track appointments, medications, labs, and follow-ups.

How you stay oriented when everything else feels uncertain.

At Texas Oncology, the system was different — a separate portal, same dependency. Different logo, same reality. These platforms vary by provider, but the relationship patients have with them is consistent: you use what you’re given, because there is no alternative.

That asymmetry matters.

Trust without negotiation

As someone who has worked in healthcare-adjacent technology, I understood the role these systems play. Large healthcare organizations rely on enterprise electronic medical record (EMR) platforms to manage clinical workflows, ensure HIPAA-compliant communication, and coordinate care across massive networks of providers.

From the patient side, though, there is no vendor selection. No consent dialogue. No meaningful opt-out.

You don’t choose the portal.

You don’t configure how data flows.

You don’t see what’s happening behind the scenes.

You trust — because you must.

And when you’re a patient, especially a vulnerable one, that trust isn’t abstract. It’s deeply personal. You’re not sharing browsing preferences or shopping habits. You’re sharing diagnoses, symptoms, lab results, fears, often at the worst moments of your life.

That’s what makes recent revelations about patient data exposure through healthcare portals so unsettling. Not because technology failed in some spectacular, cinematic way — but because the failure was quiet, systemic, and invisible to the people most affected by it.

The risk model patients inherit

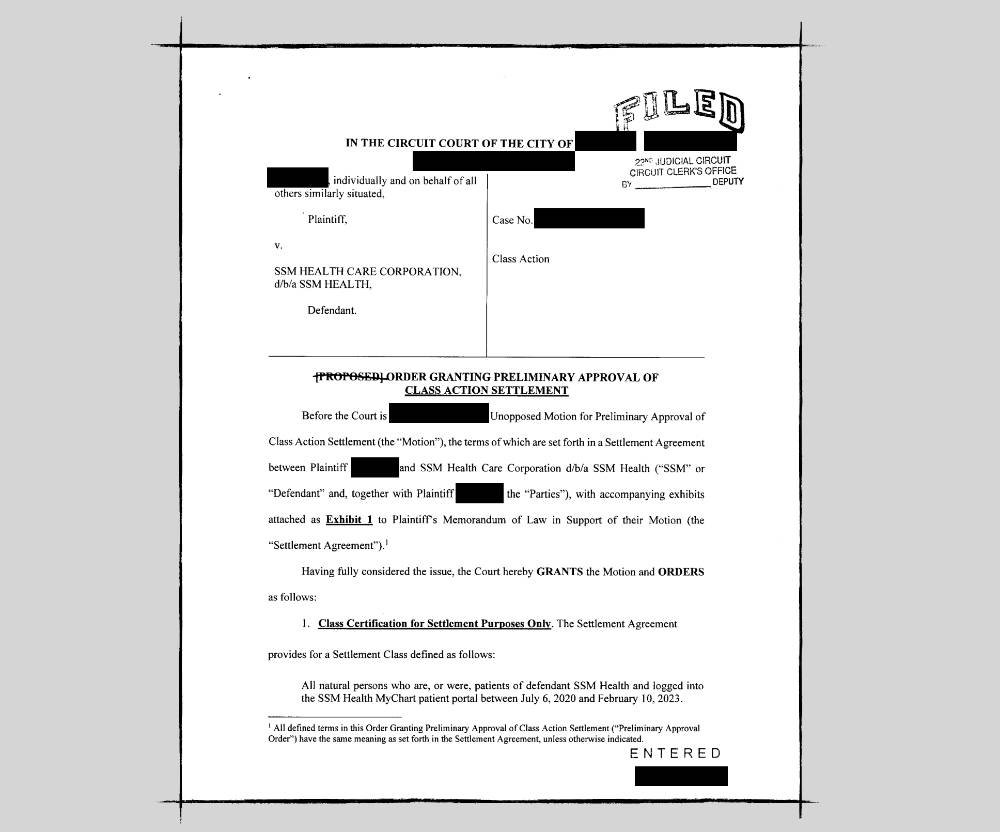

The issue at the heart of recent MyChart-related lawsuits isn’t simply whether a particular line of code violated a regulation. It’s about how risk scales when healthcare infrastructure becomes indistinguishable from data infrastructure.

Enterprise EMR platforms are designed to serve organizations first. They must support billing, reporting, analytics, compliance, integrations, and growth. Patients are users — but they are not the primary customer.

That distinction matters when decisions are made about:

-

instrumentation and analytics

-

third-party tools and tracking technologies

-

optimization, performance, and “insight”

Individually, these choices may seem benign. Collectively, they create systems where patient data can be exposed without patients ever knowing it happened.

The lawsuits outlined in the accompanying report describe scenarios where tracking technologies embedded in patient portals allegedly transmitted sensitive information to third parties — without explicit patient consent. Whether or not every allegation holds, the pattern is clear: the larger and more complex the system, the harder it becomes to ensure patient agency remains intact.

For patients, the ramifications are not theoretical. When trust erodes, it doesn’t just damage a brand — it destabilizes care.

Why vulnerability changes the equation

When you’re healthy, data privacy feels like an abstract concern.

When you’re in treatment, it’s different.

Cancer already strips away a sense of control. Your schedule, your body, your energy, your future — all feel uncertain. Digital tools are supposed to restore some agency: clarity, continuity, communication.

When those same tools quietly expose patients to additional risk, the cost isn’t just legal. It’s emotional. It’s psychological. It’s a violation layered on top of vulnerability.

And unlike consumer platforms, patients can’t simply “take their business elsewhere.” If your care team uses a particular portal, that’s the portal you use. Full stop.

That’s the core imbalance this moment reveals.

A line worth naming

Healthcare technology doesn’t need to be perfect. But it does need to be principled.

There is a line between enabling care and extracting value. Between supporting patients and treating them as data sources. Between stewardship and optimization.

When that line blurs, patients pay the price — often without ever knowing it happened.

This article isn’t about demonizing systems that many clinicians and patients depend on every day. It’s about acknowledging that scale amplifies consequences, and that trust, once broken, is extraordinarily difficult to repair in healthcare.

In the next piece, I’ll explore what happens when organizations lose sight of that responsibility — and what a patient-centered, virtuous alternative can look like when agency, privacy, and vigilance are designed in from the start.

Leave a Reply